I Spent 15 Days With The Nomadic Families And Eagle Hunters Of Western Mongolia

“They don’t know how to pack camels, they don’t know how to break horses.”

The silver medal on Amgalan Baatar’s hat marks him an honoured horse trainer of Khovd’s Mankhan sum. The royal blue janjin malgai rests atop a small Buddhist altar, next to a pink cap featuring Anna and Elsa from Frozen.

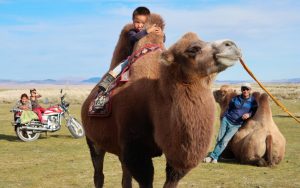

Our group’s visit is unplanned, the result of a chance encounter on our trek through western Mongolia. Even though we’re strangers, the nomad welcomes us into his ger with sweet khailmag and bowls of warm milk tea, traditionally made with water, green tea, salt and any milk except mare’s.

It’s simple fare, but I’ve had more than my fill of milk and mutton after six days in the country. Nomads aren’t much for gardening so vegetables have been scarce. I sip my goat milk tea slowly as our guide Timun interprets Amgalan Baatar’s quiet words.

“I’m worried that my kids stop following this route,” he says, referring to the unparalleled freedom of nomadic life. He fears younger generations are losing their culture as they increasingly choose more sedentary lifestyles.

Nomads, he says, have nothing to worry about. There are none of the demands, rules or expectations found in cities. Only fresh air, fresh water and the food they make with their own hands. At 62, Amgalan Baatar thinks living in a city like Ulaanbaatar or even Khovd looks difficult. It holds no allure next to life in the open air.

When one of my Western companions asks what the key to happiness is, our host answers without hesitation. “Health,” Timun interprets as Amgalan Baatar lights a cigarette.

I was initially apprehensive about travelling through Mongolia’s west. I don’t consider myself an off-road sort of person, so I feared I wouldn’t adjust well to being cut off from modern conveniences. My idea of a holiday more typically involves shopping, restaurants and functional plumbing. Mongolia was not a holiday destination I’d ever considered.

As such, I was surprised to discover what I could survive without, as well as how quickly I became comfortable with it.

It took less than a day without running water for everyone to agree that showering should be optional. Heated water was available in a makeshift shower tent on the edges of the camp, but there didn’t seem much point to regular bathing. Though clean enough, a Mongolian ger camp isn’t exactly a sterile environment, and fretting about it will do nothing but ruin your holiday.

It helped that we were all in the same situation. There was a mutual understanding that sometimes you gotta do what you gotta do, and everyone should avert their eyes during roadside toilet stops.

The sunset bathes the distant mountains in blazing orange as our two grey furgons move north. Bata, our second guide and Timun’s wife, tells us the sturdy vehicles were originally designed to be Russian military ambulances — a claim that’s easy to believe.

Earlier in the day, we climbed a steep, rugged hill to see ancient carvings discovered only in 2018. The wind pulled at our jackets as Timun, Bata and petroglyph expert Baasan Dorj debated the exact positions depicted, though everyone agreed the figures were definitely having sex.

Now we’re headed toward a ger camp at Durgun Lake after eating a home-cooked lunch of mutton dumpling soup at our driver’s home. I cradle four pieces of dried curd Narantsog’s wife pressed into my hands as we left.

A flask of vodka is passed among us passengers, bought from a small shop in Khukhmorit which sold everything from snuff bottles to curd popsicles to a single purple jumper that read “It’s not you, it’s me”. Mongolian songs blast from the radio as we drive, and we jam along without understanding a word.

A six-hour furgon ride sounds gruelling on paper, but it didn’t even take a day for us to start looking forward to climbing back into the vehicles. Nobody bothers to buckle in, though the rocky, unpaved route bounces us in our seats. The only vehicles on the trail are our own, and the flat, sweeping steppes yield almost nothing we might collide with. We drive for hours without seeing a single tree, building or road sign, trusting our drivers to know the way.

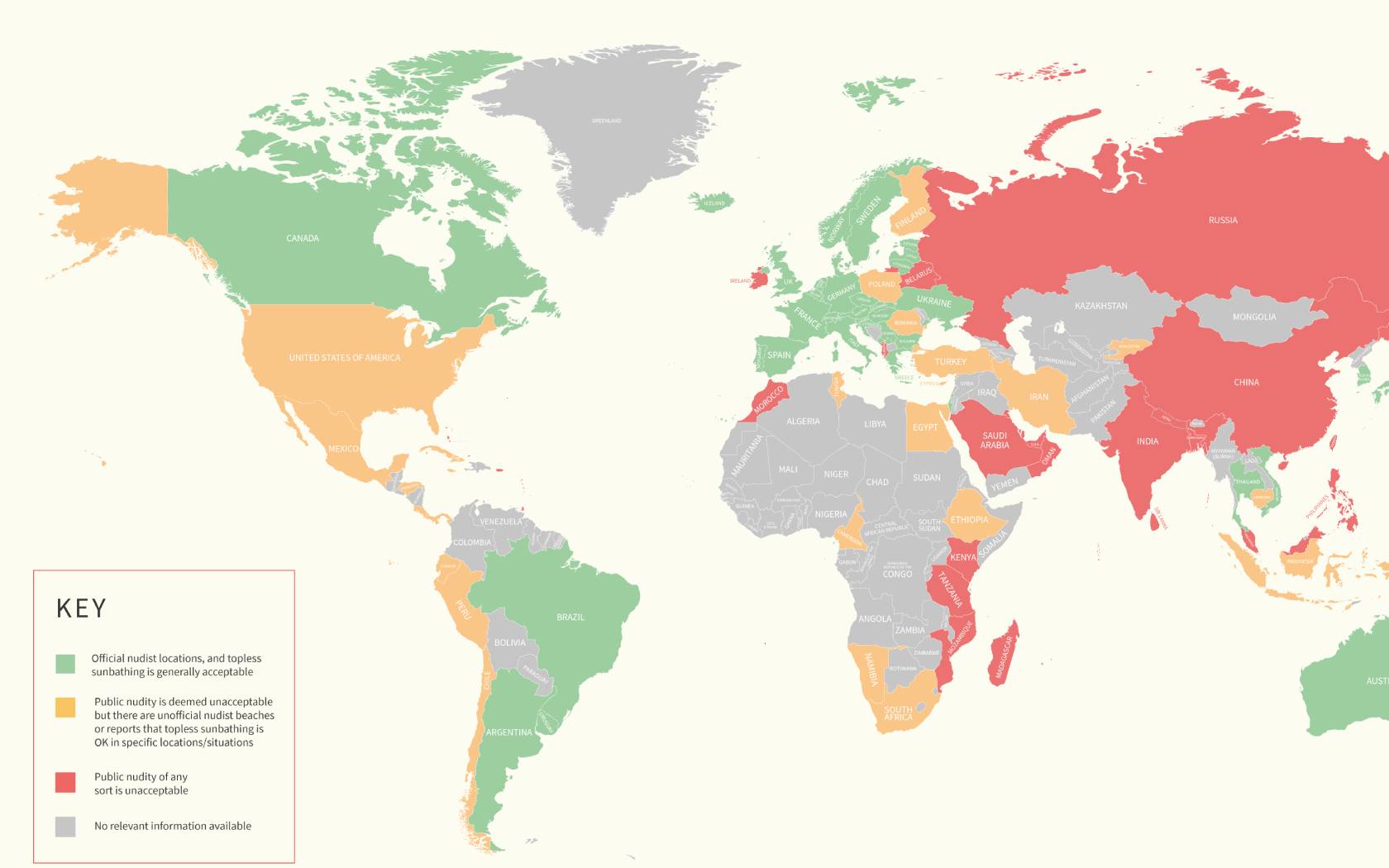

It’s impossible to tire of Mongolia’s wild landscape. Watching the steppes flow by is simultaneously stunning and soothing, and every moment demands a panorama. Riding camels across Mongolia’s largest sand dunes and searching for snow leopards in Tsagaan Sair Valley were incredible experiences, but we all came to love the long drives as much as the destinations early in the trip.

Birds of prey circle above, prompting mice and marmots to hide in their burrows. A young woman rides a white horse across the plain, her hair loose in the wind. We pass several innocuous piles of rocks, which Bata tells me are either homes for spirits or burial sites depending upon their size. It feels removed from time, unbothered and unconcerned with the industrial world of stagnant cities.

When we arrive at the Durgun Lake, the water is so calm it’s almost invisible under the star-filled sky. We stand on the gravelly shore and hunt out the North Star, waiting until after breakfast the next day to plunge in. Our guides join us but keep to the shallows. Bata says Mongolians are very good divers, but they can only do it once.

There are only three stoves at the Tsagaan Khad ger camp, so they’re given to the three foreign women in our group. The wool and dried dung burns quick but hot, its brief blaze warming my ger enough that I have to take off my woollen jumper even though we’re at over 2000m elevation.

Dinner is a Mongolian barbeque eaten with our hands, followed by an invitation to partake in vodka and song. Both are prolific wherever we go, even among the Mongolians who have settled down in towns and cities. Rather than enjoying a drink at a pub, it’s common for workers to retire to karaoke bars at the end of the day.

There are no such venues on the remote mountainside, so our hosts begin their evening right there in the dining ger. Though our group delivered a stirring rendition of ‘Wonderwall’ at a previous camp, this night I demur, still recovering from my stomach’s protest against the sudden change of diet to mutton and curd. I like red meat, but even I need a vegetable or two.

Earlier on the road, our driver Batsukh suggested I use vodka to medicate my nausea — a remedy I’d not heard of before. I don’t drink but couldn’t bear to disappoint him, so I poured a tiny shot into the cap as a compromise. This apparently wasn’t satisfactory, as he shook his head and mimed taking a swig.

Politely declining is difficult when you don’t speak the language. Fortunately, Mongolian vodka is incredibly smooth, so I thought I could manage it. “I’m trusting you on this,” I said as I lifted the bottle. Batsukh just laughed.

We assemble to leave Tsagaan Khad the next morning as the rising sun begins to illuminate snow-capped mountains. The view is so mesmerising that our departure is voluntarily delayed by over an hour. Time in western Mongolia is more of a loose guideline than a rule.

“A hero is coming! A very handsome man is coming!” We’re admiring four Kazakh eagle hunters, grand astride their horses with their fur-trimmed hats, when Timun begins shouting.

“This man is very good looking,” repeats Timun as a fifth man rides across the steppes of Sagsai sum toward us. He’s incredibly eager to impress upon us just how attractive the newcomer is. Jenisbek is 26 years old, a celebrated eagle hunter, and single.

The question is raised whether eagle hunting makes men more attractive to women, which prompts a wave of laughter — then another when the question is translated. The answer, of course, is yes. Riding across the plains, eagle held aloft, looks as powerful as it feels. And eagle hunters always have the best fur for their hats.

Turned onto the subject of romance, the hunters tell us of a game the Kazakhs play called kaz khuar — “chasing girl”. If a boy likes a girl, he’ll ask her to play this game with him. They’ll ride out one or two kilometres, giving them a lot of time alone for him to express how he feels and for her to respond. Then they’ll turn around and race back, and she has to catch him and whip him.

If she likes him back she might not try so hard, and only whip him gently. If she doesn’t, he should ride hard.

As evening falls, Amgalan Baatar’s goats gather in front of his ger to be milked. His wife lashes the animals’ necks together with experienced efficiency, helped in her work by one of their sons. The couple has nine children aged 40 to 16, though most are married and gone.

With the weather cooling, many nomads will soon move to their winter gers, still avoiding towns and cities. Stagnant families in Ulaanbaatar heat their homes with coal rather than dung, making the air in Mongolia’s capital the most polluted in the world.

Our host has enough clean air to spare, finishing his cigarette before joining us outside. He cradles his infant grandchild as their four-year-old sister milks the goats, supervised by her mother. I wonder if one day she’ll learn to break a horse.

When we drive away, Amgalan Baatar’s wife sprinkles fresh milk after us, scattered from her plastic pail with a ladle. It’s a blessing for our journey and well wishes for safe travels.

AWOL travelled to Mongolia courtesy of Intrepid Travel in 2019.

All images provided by the author.