What I Learnt About Australia On A 30,000km Solo Road Trip

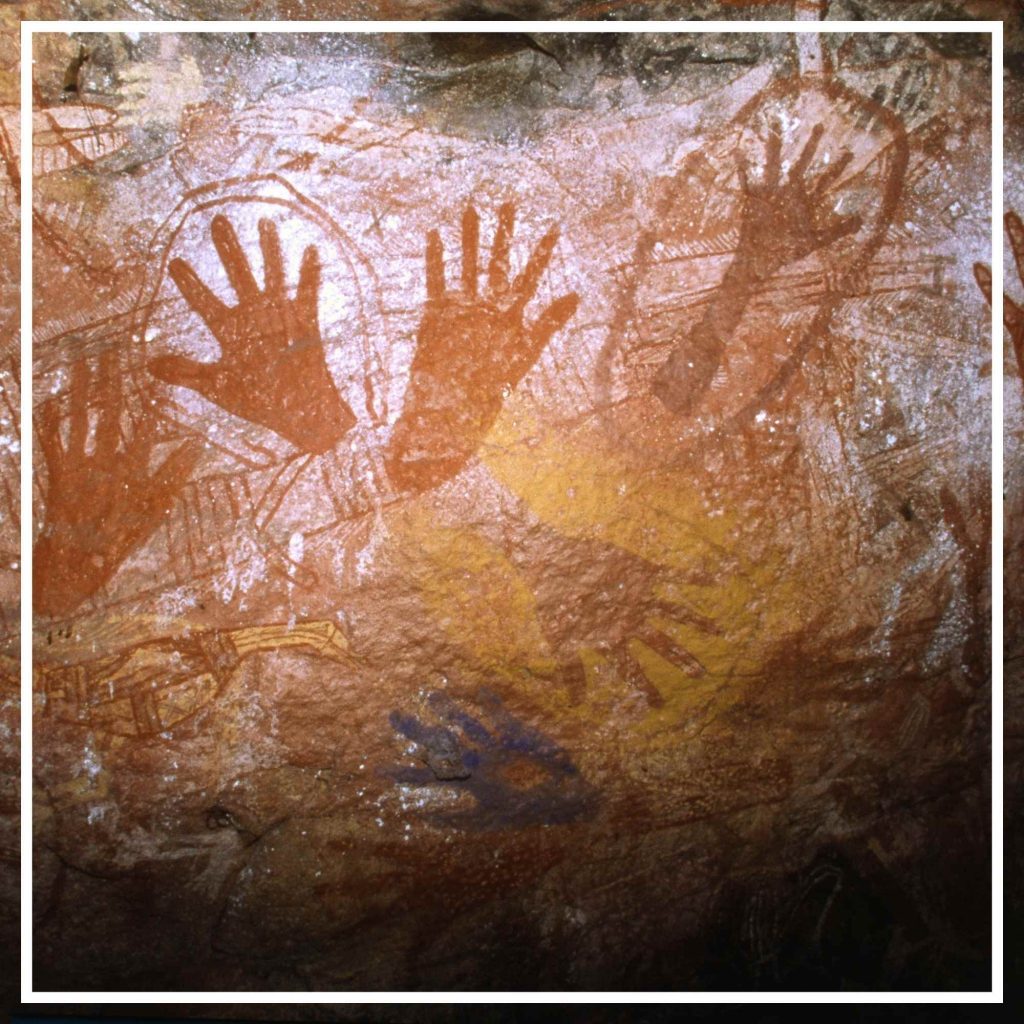

I first heard of “Murujuga” only a few years ago. A Ngarluma filmmaker visiting Sydney told me about a place in Western Australia containing one million ancient rock engravings. I was astounded. How had three decades of my life passed without hearing of such an extraordinary-sounding place, nor even its English name the Burrup Peninsula?

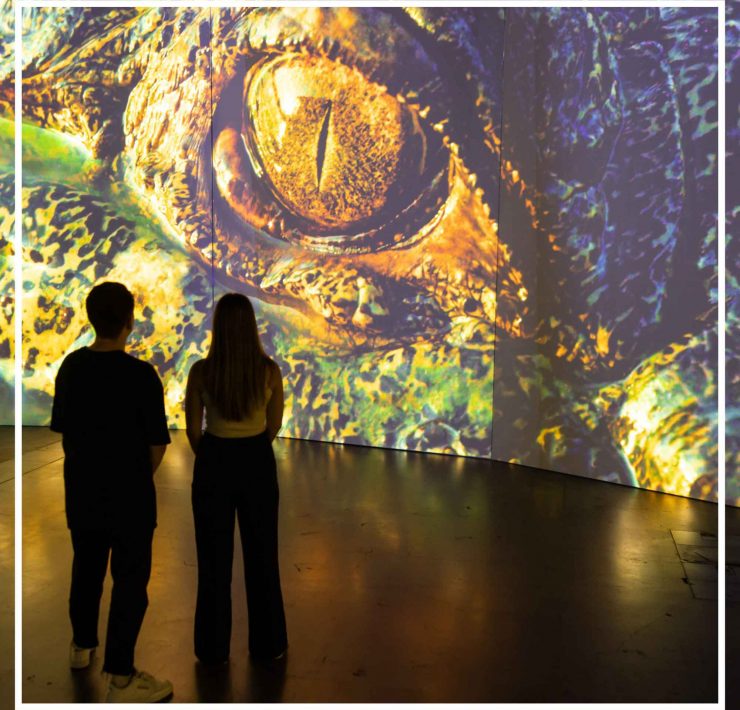

If this is the first you have heard of Murujuga, I can assure you it is extraordinary. In 2016 I took an epic 30,000km outback road trip around Australia and was lucky enough to see Murujuga myself.

Imagine colossal mounds of squarish red rock tumbling into blue waters, an archipelago whose name means “hipbone sticking out” in the local Yaburrara and Ngarluma languages. The boulders are hard as diamonds and constitute the largest and most diverse collection of rock engravings in Australia, if not the world.

I saw engravings depicting fish, eggs, human figures, bird tracks, kangaroos and, perhaps most excitingly, a thylacine. Its tail was curled in the air and head bent down, and on its back it bore those instantly recognisable Tasmanian tiger-stripes (a misnomer, for the animal once roamed the mainland).

A City Dweller Sets Out On An Outback Road Trip

Growing up in Sydney, I was not the most likely candidate to one day embark on a six-month long solo road trip, camping, fishing and birdwatching my way through the country’s remote corners. After all, I was a city slicker through and through, born to a pair of Chinese-Malaysian immigrants for whom the Aussie bush never held much appeal.

Like many young Australians my childhood consisted of a hefty diet of American and British pop culture, so post-university I was far more excited to live in the epicentres of Western culture – New York, Paris and London – than I was seeing my own country. I held vague intentions to one day see Australia when I was retired, telling myself, “It’ll always be there”.

It was only after I turned 30, and had not only spent time in the United States and the United Kingdom but in China, too, that it occurred to me there was something absurd about the fact I knew more about the American cities of Chicago, Austin and Miami than I did about Broome, Alice Springs or Cairns. That I could name more Chinese ethnic minorities, than I could Indigenous Australian nations. That I had, indeed, seen that Italy’s Tower of Pisa is leaning, yet knew nothing about the globally significant sites in our own backyard such as Mungo Lake, Uluru or Kakadu National Park.

I doubt I am alone in this because I encountered few young Australians as I travelled in my Toyota RAV4 on the dusty highways winding around this immense continent. Occasionally I met a youngish European hitchhiker, and otherwise lots and lots of grey nomads as those travelling retirees are affectionately known.

And that’s a real shame. Because holidays are fun, but travel is transformative.

And seeing my own country forever altered my relationship with Australia for the better. It’s something every young Australian needs to do now, not when they’re retired.

History Unseen

Before I went on this outback road trip, the picture of Australia in my head was probably one of the hundreds of sleepy, surf towns dotted on the east coast: predominantly white, laidback and suburban.

But the rich, complex, diverse sites of history I encountered on my travels forced me to rethink the very essence of Australia.

Take northeast Arnhem Land, where English is often spoken only as a fifth – or sixth – language. I hiked along the shoreline where for hundreds of years prior to European colonialism, Maccassan fishermen (present day Indonesia) would make their annual arrival to collect sea cucumber and trade with the Yolngu people. They would take the sea cucumber back home and sell it onwards to China where it is still considered a delicacy.

Several hours west of Arnhem Land is Darwin, which in the late 1800s was known as Palmerston. In a charming Northern Territory Chinese Museum are artefacts and photographs that demonstrate why Palmerston was once known as “The Orient in the Outback”, with its Chinese population outnumbering Europeans at least four to one.

Back then the Top End was as multicultural as Australia now. All over the country colonial sites, I learned, are not only tales of European Australia but also tales of Chinese Australians, Indian Australians, Lebanese Australians, Malay Australians and the survival of the oldest continuous culture on the planet.

Those Who Came Before

Having spent time in so many Indigenous Australian communities while out on my road trip, I began to see that perhaps I would never love anything the way First Australians loved and knew their country. That, as the first in my family to be born on this continent, I could never understand what someone with up to 60,000 years (or more) of ancestral connection to country has. That connection was best captured in words by Senator Pat Dodson when he described Country this way:

“We heard the other day land being described as ‘piece of dirt’. That would be the same as someone who considered St Peter’s just a barnyard to Catholics.

“For the Aboriginal people land is a dynamic notion. It is something that is creative. Land isn’t just bound up with geographical limitations that are placed on it by a surveyor, who marks out a plot and says: ‘This is your plot’. Land is the generative point of existence; it’s the maintenance of existence; it’s the spirit from which Aboriginal existence comes.

“It’s a living thing made up of sky, of clouds, of rivers, of trees, of the wind, of the sand, and of the Spirit that has created all those things, the Spirit that has planted my own spirit there, my own country… It’s a living entity. It belongs to me – I belong to the land. I rest in it, I come from there. Land is a notion that is most difficult to categorise in [non-Indigenous] law. It is something that is very clear in Aboriginal law.”

Kindling A Love Of Australia

But my road trip travels have also shown me that even if I will never be as intimate with the land as the First Australians, I could still learn from those who had come before me or whose ancestry had come to this continent long before mine. And with every step I took, I was being nourished and loved, completely, by the land.

By the end of my trip I came to realise that I was dizzily in love with Australia. Having walked its hills, tasted its fish, slept under its stars, traversed its many lands – from the dry, red heart of the country, to the bottle-shaped boab trees of the Kimberley and the dripping wet rainforests of far-north Queensland.

Having heard its stories and understood better its strange, wonderful and heartbreaking history, a fresh feeling of intimacy had been engendered in me. Australia, to me, was like a family member who drove me mad, or to great depths of pain, but ultimately, whom I love and am deeply committed to.

Monica Tan is the author of Stranger Country, a recount of her 30,000km, six-month solo road trip around far-flung regions of Australia.

This story was originally published on April 2nd, 2019.